POPULATION STATUS

The federally endangered red-cockaded woodpecker (RCW) is a species reliant on old and second growth pines for nesting. The RCW’s preference for longleaf pine resulted in drastic RCW population declines as nearly 90 million acres of virgin longleaf pine was logged, converted and developed since European settlement in North America. Historical population estimates for the RCW were around 1 million individuals which had dipped perilously low (< 10,000 individuals) by the mid-1900s. Consequently, it was one of the first species listed as endangered in 1968 and then protected in 1973 under the landmark Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Current population estimates are between 18,000 and 19,000 individuals or 7,800 family groups. Recent gains are attributed to intensive management of nesting and foraging habitat by wildlife biologists and land managers. Widespread use of prescribed fire, while playing a critical role in maintaining healthy and diverse longleaf pine ecosystems, has undeniably aided in RCW population recovery.

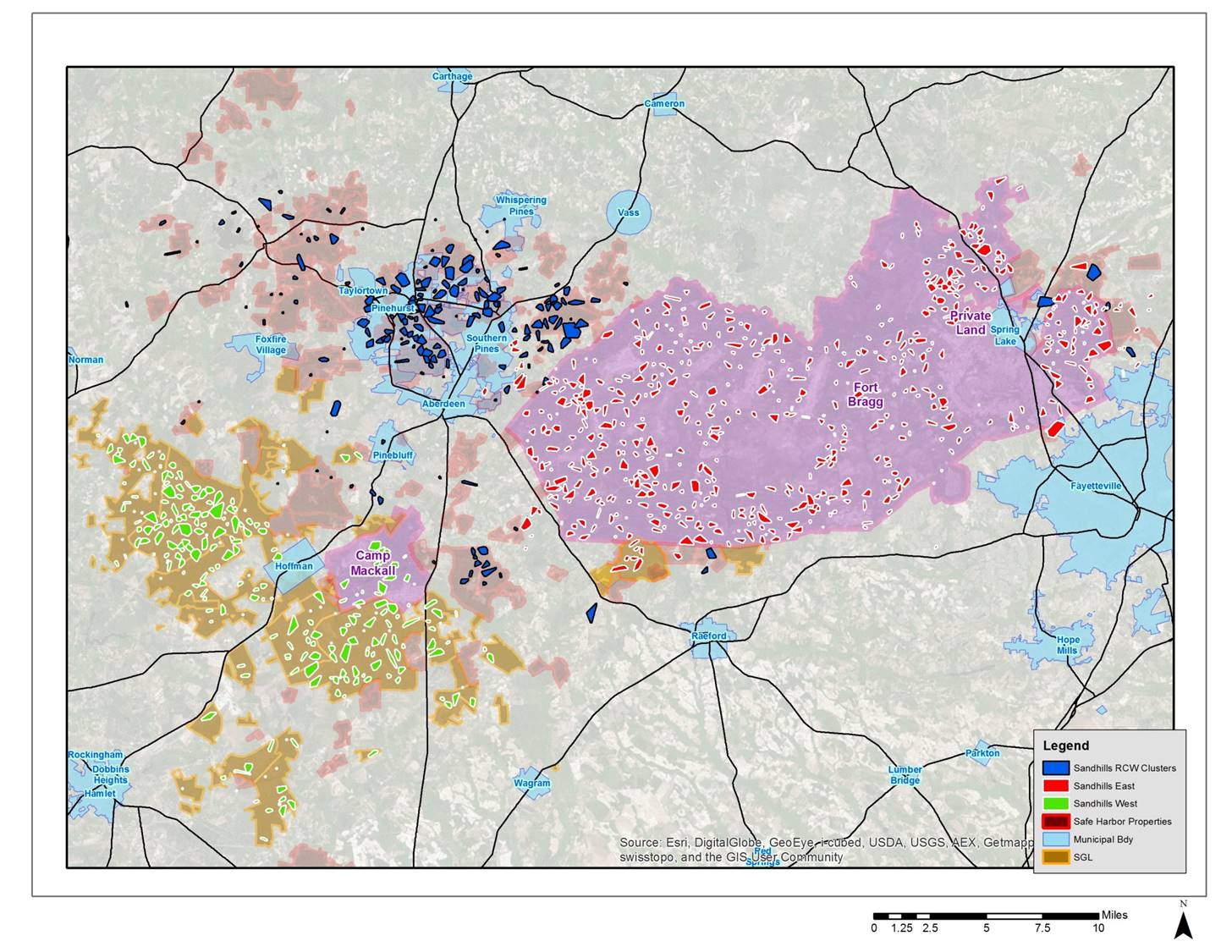

RCW in the NC Sandhills are distributed between 2 population units, Sandhills East and Sandhills West.

One of 13 Primary Core RCW Recovery Population designated across the Southeast by the US Fish & Wildlife Service is located within Sandhills East and an Essential Support Population is within Sandhills West (RCW Recovery Plan; 2nd Revision – USFWS 2003). Most RCW groups within Sandhills East occur on the federally managed Fort Bragg Military Installation in Hoke, Harnett, Moore and Cumberland Counties, North Carolina. The Southern Pines – Pinehurst (SOPI) Significant Support Population is also found in Sandhills East. Sandhills West is comprised chiefly of the Sandhills Game Land in Richmond and Scotland Counties.

The Primary Core Recovery Unit within Sandhills East achieved its’ population goal of 350 estimated potential breeding groups (PBG) in 2005. Sandhills East and West have increased in estimated PBG numbers in the last decade.

BIOLOGY

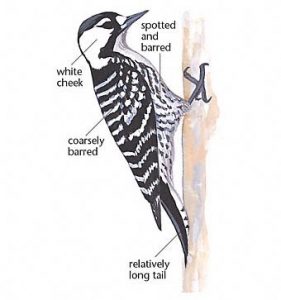

RCW are one of 8 woodpecker species known to occur in the Southeast, which can lead to confusion with identification.

(Illustrations D. SIBLEY ©)

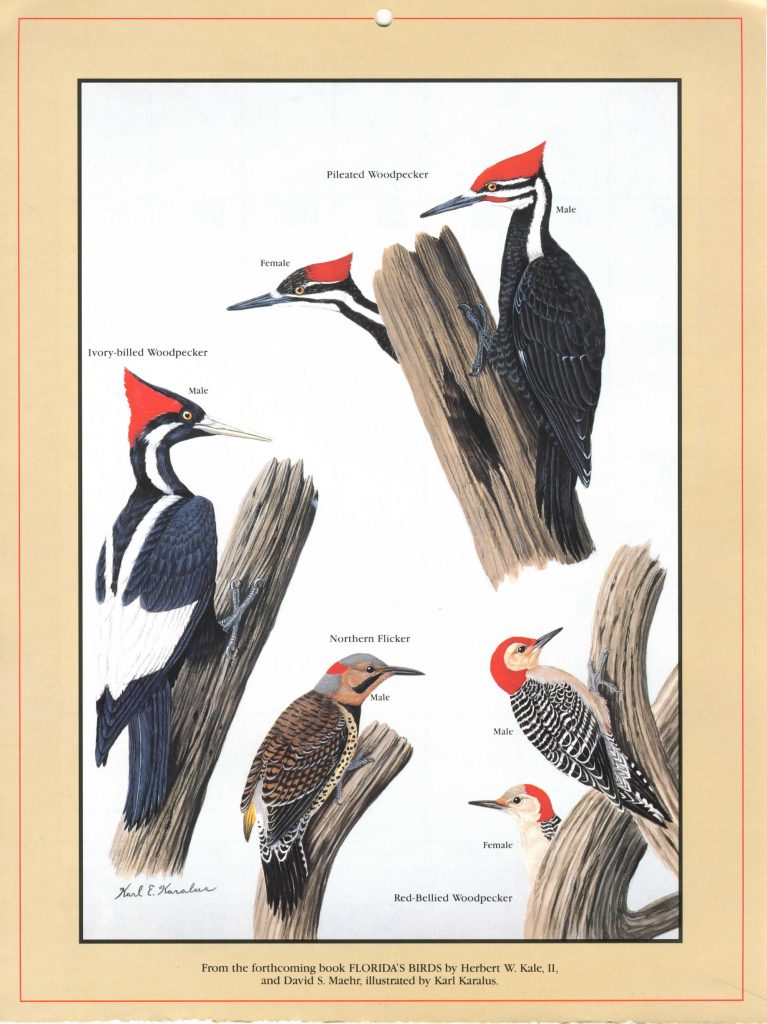

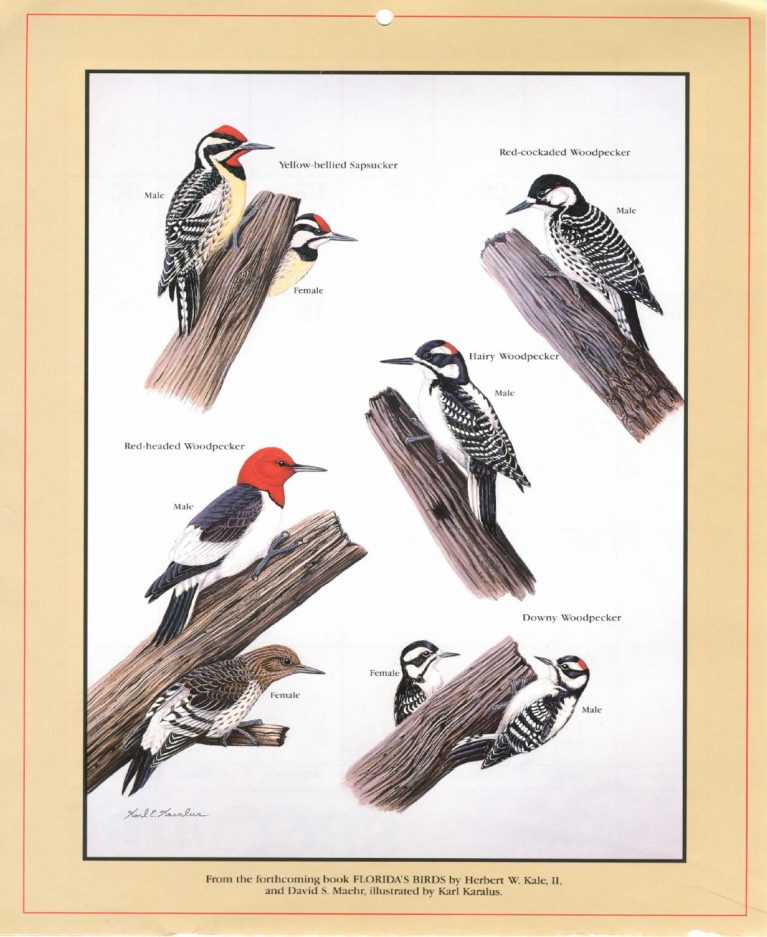

The pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus), red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus) and the red-headed woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus) possess significant red plumage and are found in close association with RCWs. These woodpeckers have more generalist habits compared to the RCW and while protected, are not threatened. Only male RCWs have a small number of red feathers, known as ‘cockades’ just above the white cheek patches on either side of the head. Many times the cockades are neither visible nor conspicuous. Juvenile males have a red-crown patch that molts into a cockade during the bird’s first year. Adult and juvenile females have no red with entirely black crowns.

Southeastern woodpecker species

Southeastern woodpecker species

(Illustrations K. KARALUS ©)

The RCW is the only North American woodpecker species that excavates a chamber or cavity exclusively in live pines, a process that can take several to 12+ years. These cavities provide a vital resource to the RCW and to a suite of secondary cavity nesting species. White-breasted nuthatches (Sitta carolinensis), tufted titmice (Baeolophus bicolor) and great-crested flycatchers (Myiarchus crinitus) are common passerines that nest in RCW cavities, while small raptors such as American kestrels (Falco sparverius) and screech owls (Megascops asio) are occasionally found in enlarged cavities. Red-headed woodpeckers, red-bellied woodpeckers, European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) and eastern bluebirds (Sialia sialis) have been known to displace and even kill RCWs to gain access to cavities. Southern flying squirrels (Glacomys volans), gray and fox squirrels (Sciurus spp.), tree climbing snakes (Pantherophis spp.), frogs and skinks are also among the 30+ vertebrate species biologists documented in RCW cavities.

The aggregate of cavity trees known as clusters (previously called colony sites) within territories is defended year round by group members. Each member of the group will roost in a separate cavity. Some groups consist simply of the breeding male and female, while others have extended families with one to several non-breeders or helpers. Nesting occurs in the breeding male’s cavity, which is generally the best quality cavity or most recently excavated. Helpers within groups delay dispersal to assist with reproduction and all members share in duties of incubation, brooding and feeding young. Helpers are generally related males although occasionally related helper females occur as well as unrelated individuals. This life history strategy is termed cooperative breeding and is observed in relatively few bird species in temperate regions. Cooperative breeding in RCWs is thought to have evolved in response to a limitation of suitable cavities for roosting and nesting.

LINKS: